“Why is this happening?”

A long time ago, I worked at Maxis, then a new addition to Electronic Arts. My focus was The Sims, but we had some conversations about the then-new SimCity 3000, including about things like placement of police stations in player’s cities. One question I asked was, why was there no downside to having too many police stations? This question was met with baffled looks: how could that possibly be a problem? I brought up issues of an overbearing police force leading to a disgruntled populace (and thus more interesting player decisions), but my questions were brushed off — in the interest of maintaining management game development scope.

Today of course this question is a bit more pointed (and might well have been at the time, had the racial and socioeconomic mix at Maxis at the time been a bit different).

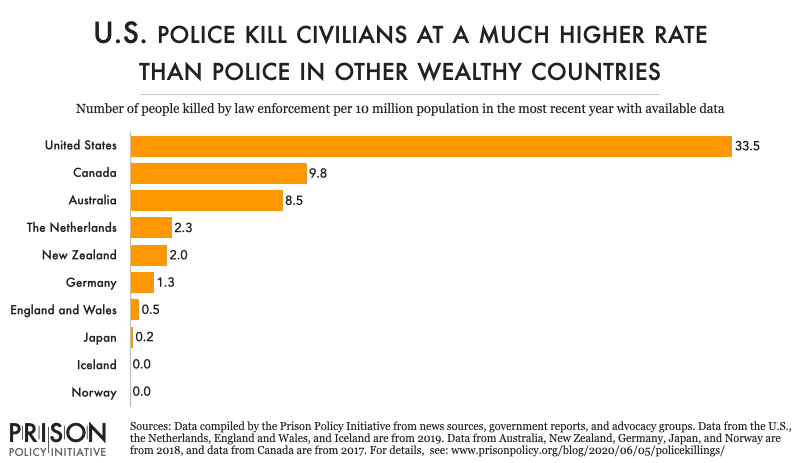

Based on the fusillade of recent killings of African-Americans by police, and in light of the statistic that police in the US kill civilians at a far higher rate than in another developed country, the understandable question has been brought up in many contexts, including recently in an online discussion: why is this happening?

Lurking behind this question (not very far behind, for many of us) is the desire for a single root cause. How can we fix it? Where is the switch we can flip, the condition we can change, to make this all go away? Can we throw money at it? Protest? Change a law? There must be something — one easy, simple, bumper-sticker worthy thing we can do to make this all better. This short-term focus is very on-brand for us in modern America.

The necessary but not entirely satisfying answer tot his question is that this is a systemic problem. That means there ISN’T one thing causing this. It also means that people are going to latch on to one particular solution or another, and they will all be wrong. So, a systemic sketch:

It’s poor training: too much reliance on force, not enough emphasis on de-escalation. As shown on video after video, many police now respond to situations assuming deadly violence as the first option, to be met with overwhelming, often deadly force in return.

As an example, the members of the “emergency response team” in Buffalo who aggressively knocked an elderly man to the ground kept marching forward rather than seeing to his welfare because they were trained to do so. Their logic seems to be that they have medics coming up quickly, so those on the front lines (fully armed and armored like modern-day Spartans, by now an old comparison) were to keep pressing forward to overwhelm any resistance. Consider the mindset behind that training. This isn’t a doctrine born of thinking about the community these police serve; it’s a military tactic executed on US citizens as if they were an enemy force.

This has many consequences ranging from law-enforcement officers coming to see those whom they encounter as something other (less) than citizens with rights first and foremost, to low-level, on-going PTSD on the part of the officers — with sad but predictable consequences ranging from domestic abuse to being in constant fight-or-flight mode.

It’s militarization: Many police departments have gotten millions of dollars in free, offensive hardware from the DoD. This helps justify our massive military budget and the amount of jobs we have tied up in producing offensive, not defensive, hardware that’s then given to police. (This program was curtailed by President Obama in 2015, and brought back by President Trump in 2017.)

It’s community alienation: reverberations of enforced segregation remain in cities with food deserts, lack of services, loss of economic participation, and resulting loss of hope. This in turn brings on increases in crimes of hopelessness, especially high-dollar ones centered on drugs, which bring in the threat of violence, and which police (see above) react to with increased force rather than treatment and de-escalation.

The other half of community alienation is that all those participating in the primary economy (pretty much anyone reading this) want to keep those who aren’t doing so as far away as possible, and as controlled as possible. Systemic racism lives here too, even if those benefiting from it don’t realize it and even abhor it: for them (us) it’s not about someone’s skin color, but about their lawlessness and violence, which must be kept as far away as possible — even if that lawlessness and violence itself is reinforced by the background systemic racism that benefits those deploring it!

It’s the prevalence and mobility of guns in America. As just one example, guns are difficult to get legally in Chicago (and Illinois in general), so those more concerned about maintaining their money and power in an economy set up against them (see community alienation above) simply bring them in from Indiana, right next door, where it’s easy to get them. This gives the police all the reason they need to militarize (see above) to meet this perceived threat.

It’s the siege mentality of police, who do a job where every single day they and their loved ones know they may not come home. They have to arrive at every single call assuming the worst, and to make split-second life-altering decisions day after day, as the police have become the dumping ground for dealing with everything from someone having a mental illness crisis to a domestic dispute to a neighborhood argument to a rape or murder.

If they make an error in judgment it means the end of their career (something shared by, say, doctors and airline pilots). In addition however, each officer knows that if someone near them makes an error in real-time judgment, they risk being injured or killed themselves. If they don’t report such an error (small or large), they lose their integrity. But if they do report it, they may be seen as a traitor to those who share their dangerous job, and lose what protection they have from dealing with what often seems to be an angry, violent, armed populace. This mentality relates back to poor training and community alienation (above), and is highlighted in the “blue wall of silence” where police close ranks to protect each other, inevitably separating them from the communities they theoretically serve.

There are certainly other major contributors this quick sketch misses as well.

NONE OF THIS is in any way is meant to justify any of the unconscionable behavior we see over and over again on the part of some — too many — members of law enforcement. It may however be a beginning of understanding and breaking down this system of deeply interconnected phenomena. There is no root cause.

If we look for single root-causes, we’ve lost already. We need instead to look for high-leverage areas for change, and then find ways to build on that, reinforcing the positive effects we begin to see. There are examples of this we can point to already in the actions of cities like Camden NJ, Eugene OR, Richmond CA, and elsewhere: in these cities changes to police culture, training, community involvement, separation of calls (so police aren’t responsible for responding to everything), and other measures — all working together — have made for a great deal of positive change.

I hope that we as a society are able to do this across our nation. The first step however is to stop looking for fast, easy, single root causes. They don’t exist.

Recent Comments